A grey afternoon in Tehran begins with the growl of thousands of vehicles. Yet beneath the familiar bustle lies a troubling transformation: the government has quietly shifted much of the country’s mobility onto low‑octane, additive‑laden petrol. Confidential data from the national refining and distribution company reveal that consumption of sub‑standard “ordinary” fuel has soared — with consequences for public health and the environment.

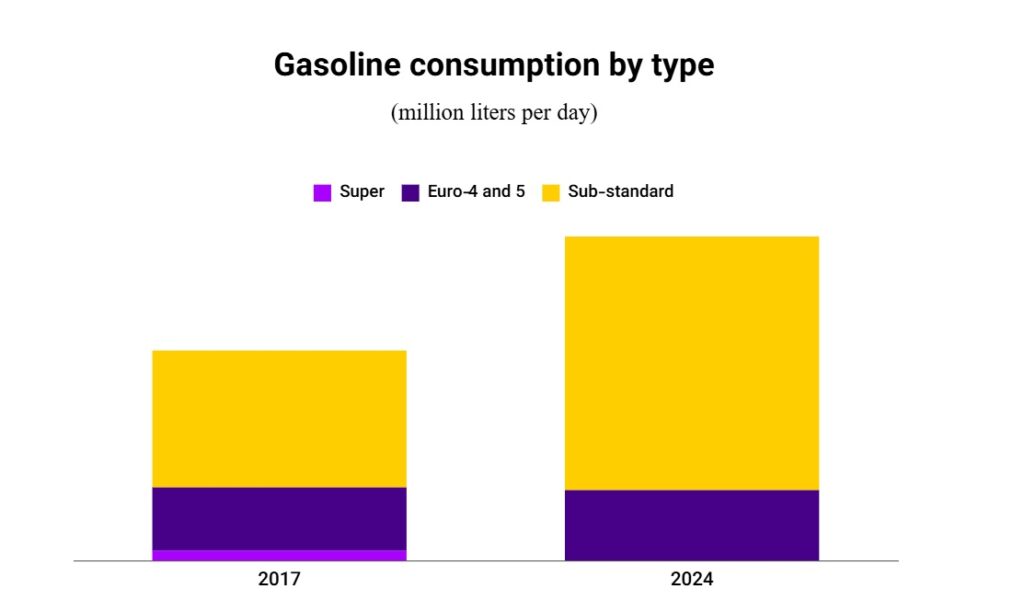

Between 2015 and 2024, daily petrol consumption jumped from about 75 million litres to 124 million — an increase of roughly 65 per cent. Over the same period, the share of low‑octane (octane 87) fuel rose from around 65 per cent in 2017 to nearly 78 per cent today. The bulk of this growth, in other words, has been fuelled by cheap, dirty petrol — not cleaner alternatives.

The mix at the pump has shifted sharply. Sales of higher‑grade fuel — from “super” premium to Euro‑4 and Euro‑5 petrol — have collapsed. “Super” petrol dropped from 3.74 million litres/day in 2017 to just 164,000 litres/day in 2025 — a 96 per cent fall. Of that, about 71 per cent is consumed in Tehran. Euro‑4 and Euro‑5 grades are now distributed in only 12 provinces, totalling around 27 million litres/day nationwide.

Meanwhile, the share of petrochemical additives — particularly ether oxygenates like Methyl tert‑butyl ether (MTBE) — has reportedly quadrupled between 2022 and 2025, further polluting an already dubious fuel supply.

A reversal of global fuel‑quality norms

This shift is not simply about domestic economics. In many countries MTBE has been phased out or tightly restricted due to its environmental and health risks. It is highly soluble in water, persistent in the environment, and capable of migrating into groundwater. Repeated incidents of MTBE contamination have led to costly cleanup efforts in wells and aquifers.

Short‑term exposure to MTBE — often via inhaled vapours — has been linked to nausea, respiratory irritation and neurological symptoms. As much of the world tightens standards, Iran appears to be heading the other way: doubling down on the cheapest and dirtiest option.

The provincial dimension

Between 2022 and 2023, use of octane‑87 fuel rose 13.2 per cent year‑on‑year across 31 provinces, reaching 97.1 million litres/day. The steepest increases were in Tehran and the central provinces — suggesting the trend is not confined to rural or underdeveloped areas but is reshaping fuel consumption in major urban centres.

This is more than a data point. It marks a structural shift. As cleaner fuel grades vanish, consumers — often unaware of the chemical downgrade — are increasingly reliant on a petrol mix that would be considered unfit in much of the developed world.

Policy through obscurity

The data come from internal reports of the state‑owned refining and distribution company. There has been no public awareness campaign, no environmental assessment, and no plan to mitigate health risks. The shift unfolded quietly — even as consumption soared and air quality worsened.

One might expect policymakers to expand access to cleaner petrol or reinforce standards compliance. Instead, they have retrenched: embracing the cheapest, most polluting grades, while rebranding them as “Euro‑4”, “Euro‑5” or “super” — despite the additive contents that render those labels technically misleading.

For now, the country’s fuel strategy is clear: burn more, burn dirtier — and label it ‘super’.

The article was published on Iran Open Data